By Bernard E. Harcourt

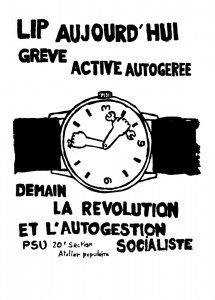

For a period in 1973-74, the worker occupation and autogestion of the Lip watch and clock factory in Besançon, France, became the most promising and exciting revolutionary experiment in post-capitalist industrial organization in France and abroad.

The Lip factory was home to over a thousand workers in a technologically-advanced, state-of-the-art, Taylorist watch production factory that had been built over decades of industrial innovation. The factory operated well, but with the advent of quartz watches in 1973 (which Lip also began to manufacture) and a growing equity ownership by the Swiss watch company Ebauches S.A. (the subsidiary of the large Swiss consortium that would later become Swatch), the Lip factory was slated to be downsized. The Lip company went into bankruptcy, and the Swiss company planned to restructure the factory, proposing to lay off hundreds of workers.

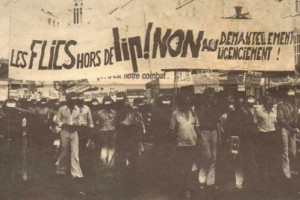

The workers, many of whom were already unionized with the CFDT (large Christian union, secularized) and the CGT (large communist union), began to assemble in action committees and general assemblies, and stumbled on management’s plan “to get rid of” (dégager) about 450 workers. When the information became known, the factory workers first planned a work slowdown to protest the impending layoffs, but eventually the workers occupied the factory and held the directors hostage as they prepared to negotiate for their continued subsistence. The workers were expelled from the factory and the hostages released through a repressive police assault by the CRS (French paramilitarized police).

In response, the workers organized among themselves—outside the bounds of their union representatives and union tactics—and decided to take hostage the entire inventory of Lip watches, which consisted of approximately 60,000 to 80,000 watches, and the company’s treasury, which was a significant sum of French Francs. Through informal mechanisms similar to the French resistance, they hid the watches and the money in various locations in the region, as a way to give them leverage in their negotiations.

The negotiations broke down, and eventually the workers—deliberating together in general assemblies, beyond the framework of the typical union leadership—decided to start operating the factory on their own. Their experiment in autogestion and self-governance of the factory became a rallying cry for post May ’68 France. They operated the factory on their own, with more egalitarian forms of organization, more gender consciousness as well, and became a prefigurative model of what might come after capitalism. They began to receive nationwide and global media attention, as volunteers streamed in to participate in the cooperative and visitors flooded the factory to understand how they were able to function—including the young Étienne Balibar! A high point was reached when they were able to actually sell watches, make revenue, and pay themselves a salary.

Ultimately, the French government intervened and negotiated with the workers to put in place a management team. A more progressive leadership took over and resumed the operations of the factory, slowly rehiring all 831 factory workers who had participated in the cooperative.

At the end of the day, though, with the election of President Giscard d’Estaing in 1974, a neoliberal in the mold of Thatcher and Reagan, the new government targeted the factory because of its history of worker cooperation. The government kneecapped the operations and forced the closure of the factory. There were further experiments with cooperative operation of the factory during the years that followed.

The worker uprisings at the Lip factory remain a source of inspiration for cooperation, but also represent a laboratory or constellation of different forms of solidaristic cooperation that could take place in that context. What is so interesting is the way in which the different forms coexisted and interacted, including:

- more traditional syndicalist top-down, leaderful, hierarchical, and highly structured organizing by different unions, each of which hadg their own ethos and culture (including the CGT, which was a communist led union, and the CFDT, which was a secularized, previously Christian union with its own quasi congregational culture);

- more organic autogestion approaches that emphasized collective decisionmaking by all the workers reunited in general assemblies and demanding forms of consensus among everyone up and down the worker ranks;

- more rogue, militant, even illegal actions by the workers, acting outside the scope of their union leaders but coordinating among themselves, like occupying the factory, taking the managers hostage, and then taking the inventory of 60,000 watches “hostage”;

- elements of an organic worker cooperative, when the general assembly decides to get the factory back up and operating, to resume certain work functions such as assembling the existing watch parts into completed watches and selling them and the stock (they must have sold about 40,000 watches from the inventory), making it possible for the factory to operate at a profit and allowing them to pay themselves a “wild” salary, which they decided on themselves; this is what led to the famous slogan “on fabrique, on vent, on se paye” (we manufacture, we sell, we pay ourselves”) and what allowed them to pay themselves an autonomous salary for several months;

- elements of traditional, classic class struggle, which one can hear well in the comments of the CFDT organizer, Charles Piaget, when he disrupts the state-appointed labor negotiator during a general assembly to tell him, over the loud speakers, that the managers need to understand that they are dealing with human lives and not simply profit; or when the newly appointed progressive CEO, Claude Neuschwander, states that class conflict is intractable, that there simply are two classes, and that there can be no cooperation between the management and the workers, that it can only be class struggle;

- and finally, speaking of which, elements of a French socialist managerial style, captured by Michel Rocard (later Prime Minister under Mitterrand) and especially by Neuschwander: kind of paternalistic socialism that functions within set rules of class relations, almost perpetuating the class conflic in a regularized mode of management versus worker negotiations for the distribution of profit.

Perhaps one of the most stunning moments in the film is when Neuschwander, who self-identifies as a Rocardian socialist, states that there is no possibility of cooperation between the managerial class and the workers. He adamantly stated that they were of different classes and that classes are real. He resolutely said that there will never be cooperation between the two. Despite that, he had a progressive mode of management and presented as a man of the people. What his persona captured was precisely the way in which French socialism could become an institutionalized process that did not overcome class conflict, but regulated it, placed it within a perfectly regulated context in which the two classes fought for their interests in a rule-bound way and negotiated the distribution of profit. In that vision of the world, there is no cooperation possible.

The experience at the Lip factory was a laboratory, a mishmash, a bricolage, a constellation of many different forms of worker organizing. That is what makes it so interesting and such a useful example for us to include in our conversation on forms of cooperation.

And to bring us full circle, one of the leaders of the worker’s movement and autogestion at the Lip factory was a Dominican friar by the name of Jean Raguenès. He now lives in Brazil and works with the Landless Workers’ Movement (MST)!

Resources regarding the history of the worker movement, the occupation, and the autogestion of the cooperative at the Lip factory include the following, in addition to the documentary that we will be watching by Christian Rouaud, Les Lip, l’imagination au pouvoir (2007):

- Donald Reid, Opening the Gates: The Lip Affair, 1968–1981 (New York: Verso, 2018)

- René Solis, “Lip Lip Lip hourra!,” Libération, 20 March 2007

- Bernard Ravenel, “Leçons d’autogestion. Entretien avec Charles Piaget, figure de la lutte des Lip”, here.